“What happened to media literacy?“

You might see this phrase peppered around comment sections across social media and discussion forums. A phrase often thrown out by those opposite of the “it’s not that deep” crowd. People who invoke this question are asking for people to engage in more critical thought about what they are consuming, and engage with ideas and concepts beyond the surface level. But what exactly is media literacy? And how do we improve it?

What is media literacy?

You might see the word ‘literacy’ tacked on to the end of several phrases. A comprehensive definition of literacy comes from the International Literacy Association:

“The ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, compute, and communicate using visual, audible, and digital materials across disciplines and in any context”

So we might understand media literacy as the ability to identify, understand, interpret … media communication. I would definitely add ‘analyze’ to that list, especially in the context of media. Do we need to define media? Media can refer to any form of mass communication, think books, newspapers, the internet, music, radio, talk shows, movies, etc. Putting all this together then, media literacy is the ability to identify, understand, interpret, and analyze the materials of mass communication including books, newspapers, online content, movies, and more. So what is the weak link? Why are there calls for more media literacy?

The Rise of Anti-Intellectualism

Something I’ll explore in future content is the apparent rise of anti-intellectualism. I don’t want to point fingers and discuss why the current rise is happening in the first place but rather its connection to media literacy. Media literacy, as discussed later, is a set of skills that tend to weaken the less they are used. Think of your brain as a muscle, it needs to be trained and used every day. Social media has really wreaked havoc on our media literacy skills, which is why more than ever we need to be working to ensure that these skills are taught and encouraged. Anti-intellectualism is movement which is opposed to intellectualism (very aptly named) and broadly against education and science. It is often a tool of populism, defining an “us” (in this case ‘free thinkers’ or ‘regular people’) against a “them” (in this case ‘elites’ or ‘the ivory tower’). There are certainly levels to anti-intellectualism, a lot of what I’ve seen on the internet lately has been a mockery of people ‘caring too much’ or ‘reading too deeply into things’. On the surface these complaints may seem small, but shutting down discourse in these small ways is a stepping stone to stronger beliefs, such as that scientists are lying about vaccine efficacy to control the population. Don’t want to fall down the anti-intellectual rabbit hole? Then let’s look at some media literacy skills in the next section.

7 Media Literacy Skills

Media analysis tends to get a bad wrap because of our experiences with high school English classes and the obsession with finding metaphor and symbolism in the most mundane texts. So let’s step away from the ‘curtains are blue’ debate and turn to the more foundational aspects of media analysis. Wikipedia provides a wonderful list of example of media literacy which we can explore:

- Reflecting on one’s media choices

Reflecting on choices doesn’t have to be an arduous task. It can merely involve questioning which sources you rely on for news, which types of programs do you turn to for entertainment, which social media channels do you use. While these might not be the most exciting questions, nor necessarily result in big revelations, it is an important first step. There’s no demand that you change these habits and choices, but I think you need to understand what you consume, maybe where your consumption habits come from, to understand your position in the media landscape. Depending on what you consume you may be more prone to falling for undisclosed ads or perpetuating stereotypes, so reflection is a key first step as we move further down this list.

- Identifying sponsored content

This skill is very important, and one that sadly many people struggle with, young and old. I think generally, older people have an easier time spotting sponsored content because they understand when someone is trying to sell to them. However, influencers are getting more skilled in skirting regulations – or straight up violating them. This can be dangerous with undisclosed sponsorships, where people, especially children, might not realize they are being sold something.

- Recognizing stereotypes

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines a stereotype as

“something conforming to a fixed or general pattern, especially : a standardized mental picture that is held in common by members of a group and that represents an oversimplified opinion, prejudiced attitude, or uncritical judgment.”

Recognizing stereotypes is an important part of media literacy because it encourages viewers to understand how a piece of media wants us to feel about certain groups and issues. By reducing groups of people to stereotypes, it is easier to make generalizations about how they act and how they will interact with policies. Stereotypes can run the gamut in pervasiveness and offensiveness, and in fact there are probably stereotypes you might not even know about or are conscious of. The goal is to think about repeated characteristics or opinions about groups. When Jewish characters are consistently profiled as money-hungry or wealthy, it speaks to an antisemitic stereotype. Of course it can also work by way of appearance, if Black women in media are consistently shown with wigs or extensions rather than natural hair, it can create a stereotype around natural hair being undesirable or unprofessional. Stereotypes, intended or not, exist in media and it’s important to recognize them. Further you can also assess whether the stereotypes were used intentionally in a satirical way or whether it was ignorance. It can be hard to assess that line, but I think it is a good skill to exercise in critical thinking.

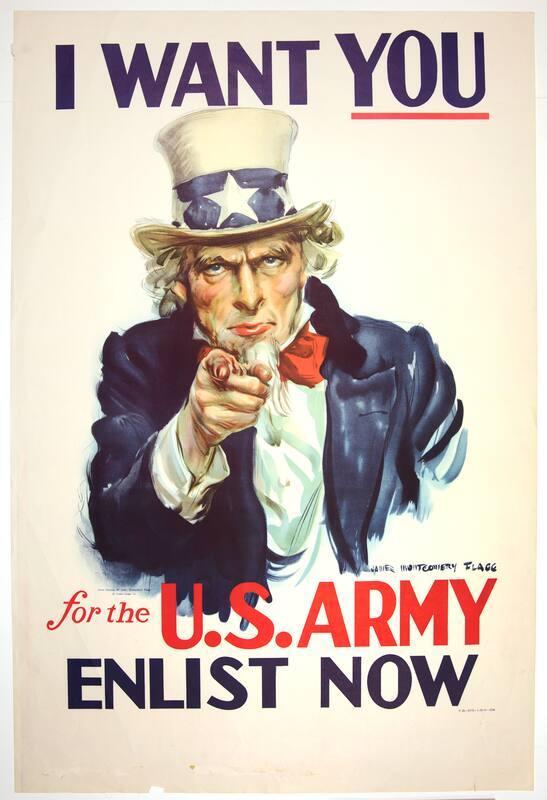

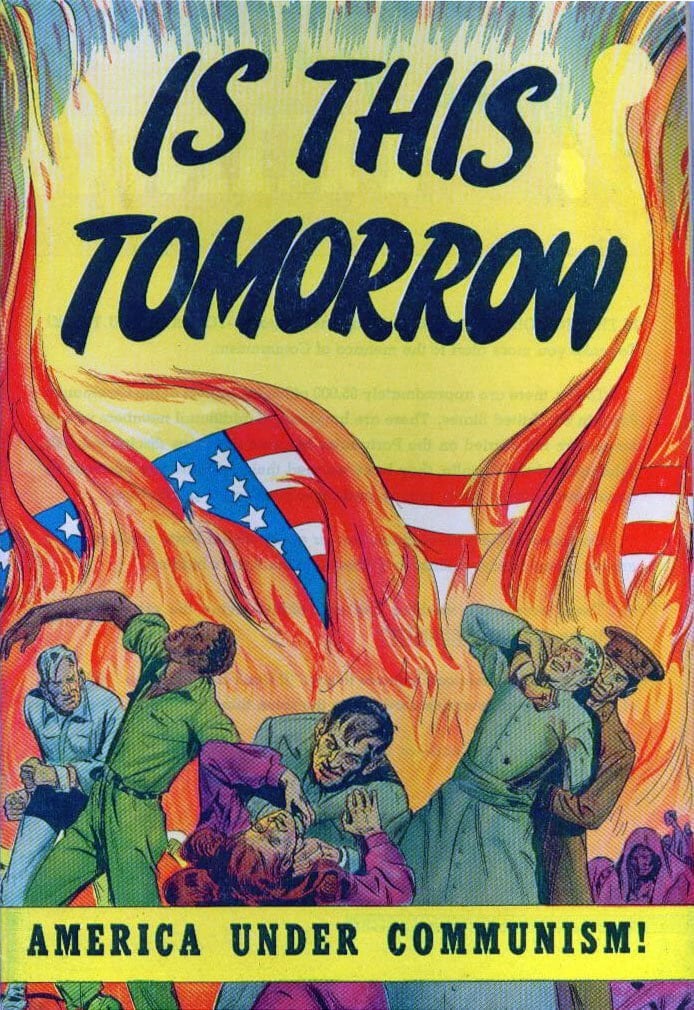

- Analyzing propaganda

Propaganda – the favourite pejorative of all political commentators – is something worth taking the time to dissect. Oxford Languages provides a brief definition of “information, especially of a biased or misleading nature, used to promote a particular cause, doctrine, or point of view” and Britannica defines it as the “dissemination of information—facts, arguments, rumours, half-truths, or lies—to influence public opinion … often conveyed through mass media”. Defining and talking about propaganda can be tricky, because as we can see from these definitions, it can be rooted in fact or lies. Here the intention of the information is the key, for something to be propaganda it must be used to promote a point of view or influence the public opinion. Can anyone create propaganda? I suppose in theory yes, however the role of power is important. Propaganda is useful in the hands of those already powerful, governments, politicians, corporations, influencers. In other words, people who have the resources to assess whether they’re sharing half-truths and have easy access to promotion through mass media. The average person may be able to promote their own propaganda through social media networks, however, without the backing of an institution the messaging could fall flat. Either way it is important to be discerning with any content created by corporations and political entities.

- Critical analysis skills

I’ve seen a lot of pushback against the use of critical analysis, particularly from BookTok spheres that ask “to let people enjoy things” as a response to comments discussing problematic passages, characters, or the author’s background. Critical analysis, in my opinion, does not mean that you cannot enjoy content that is in some form ‘problematic’ and reading or watching things with a critical lens does not make it less enjoyable. That said, the ‘critiquers’ can stop pretending that we don’t all have ‘problematic faves’, but if you’re going to platform media, it is best to be critical of the content and/or creator before giving it your seal of approval. I personally don’t feel any qualms about loving classic literature, because I engage with it critically and can identify stereotypes, harmful attitudes, and other biases that come through the writing. Stories can still be enjoyable! Some questions you can ask yourself while engaging in critical analysis (it eventually becomes second nature):

- If you’re into numbers, try a quantitative approach:

- How many characters are women vs men?

- How much screen times do Black characters get relative to white characters?

- How many books do I read with visibly LGBTQ+ characters?

- If you’re more into the qualitative approach:

- What kind of visuals are portrayed? Are characters shown in particular colours? (Think about that yellow/orange filter movies often use to depict African, Middle Eastern, and South Asian cities).

- How is dialogue written for different characters? Is it written in dialects? What is the purpose of this?

- How is music used to evoke certain emotions?

- What symbols are used and why?

- Lateral reading

Lateral reading is a method to substantiate whether something is ‘true’ or not. For example, if you watch a documentary that makes a claim about how dangerous parabens are, you can either take that as fact or you can question that claim and look for other sources to validate or challenge that belief. Now here we run into the issue of expertise and where to find reliable information, but let’s put a pin in that. So let’s say in our example that our next move is to look at what the FDA has to say about parabens (or some other governing body invested in health research). They claim that parabens are safe. Then you might move to a research institution, such as a major university, they also side with the FDA. By reading laterally, we are able to combat that misinformation in the documentary. Yay! But here is why this is a tricky method… anyone can make a website. And they can, they will, and they have. As long as there’s money in snake oil, anyone will create a website to sow disinformation and turn a profit. If you choose to avoid the FDA (who wants the government telling them what to do?) and you ignore peer-reviewed research institutions (they’re paid for by big pharma), then you will be pushed into trusting any well-designed website, by a creator that seems trustworthy. This makes lateral reading a difficult pathway to endorse, because it needs to come after learning how to properly vet a source, but in the age of conspiracy theories it can be very easy to scare people away from experts.

- Vetting sources

Finding good sources can be difficult. In the rise of anti-intellectualism, people are putting less stock in experts as well as institutions. There is a desire to find ‘smart’ people who ‘tell the truth’. Charisma plays a large role and well-equipped communicators can simply build on people’s fears and distrust of government or experts. So how can we vet our sources? Who should we trust?

Vetting sources is typically most difficult with what we call Secondary Sources. Secondary Sources are those which “analyzes, describes, or evaluates (primary) sources” (Scribbr). Anyone can produce a secondary source which makes it important to know who to trust. Primary Sources can also be manipulated but tend to be produced by institutions or something that many people witnessed (think statistics from an organization or government, interviews, news reporting, speeches).

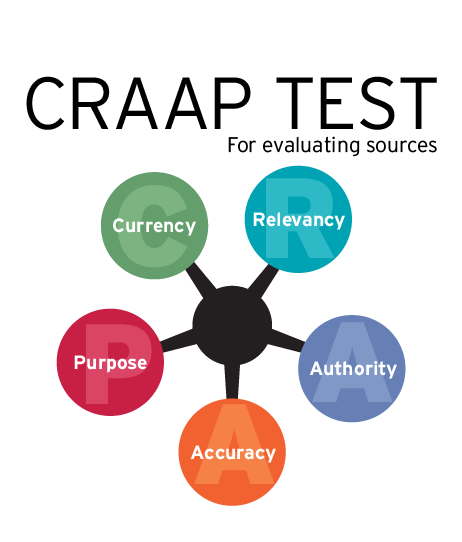

California State University came up with the CRAAP test to assess sources:

Currency: how old is the source? Is information updated regularly?

Sources don’t necessarily need to be constantly updated, but consider whether what you need requires recent sources. Articles about historical events are probably safe, we’re not often finding new sources to update our understandings. But if you want diet studies backed by science, its probably wise to look for very recent sources who have assessed new studies in their findings.

Relevance: is it a relevant source to answer your question? Who was it written for?

If you’re looking for healthy diets for student athletes and you’ve found yourself on a website promoting the Mediterranean Diet for people with heart disease, then maybe you’re not on the most relevant page (unless you also have heart disease; this is just a random example).

Authority: Who wrote it? What is their experience/credentials? Consider the URL → is it a .org, .gov, or .com?

Look for credentials. Maybe you don’t trust “experts”, but at least consider what level of training or experience someone has in an industry. The person giving you diet advice, are they claiming to be a dietician or nutritionist? What education do they have? Are they someone with experience in athletics who then pivoted to diet advice? Is the blog or website you’re reading cited by others and if so, who? None of these are ‘deal breakers’ per se, but its important to know the baggage that comes from each influencer or expert.

Accuracy: Do they cite their sources? Can you find other sources with similar claims? What tone is it written in (disparaging comments, fear mongering)?

Presentation of alternatives. A good source will usually present other perspectives, and generally if the source’s arguments are good, they will present these perspectives neutrally, rather than emotionally and with fear mongering.

Purpose: Why was it written (to persuade? To educate? To sell something?)? Is the source sponsored? Is the writing biased towards a political, religious, personal etc viewpoint?

The first thing to assess is whether this source is trying to sell you something. This can be super subtle, not necessary an ad at the bottom of the article but maybe a “Shop” tab elsewhere on the website. If you’re reading an article that tells you to stop eating a certain type of food and then recommends a vitamin or supplement to ‘keep you healthy’, that source is probably making money off of you buying those vitamins.

Sponsors. Usually, if an influencer, blog or website is financially supported by a sponsor, this information will be disclosed somewhere on the website, and its probably hard to locate. But always check ‘about us’ or ‘contact’ pages to see if a source has ties to known political entities like think tanks or foundations. The person you might trust, might be getting a paycheck from the Heritage Foundation to create content encouraging ‘traditional values’, so maybe they wouldn’t be the best source to learn about queer health care.

I think the CRAAP test is a fine tool and framework, especially to educational institutions who want to teach media literacy in a consistent way. Combine these with the technique of lateral reading and critical reading and I think you’re well equipped to analyze media of all sorts.

“Okay but what are some good sources?“

Encyclopedias! Yes the many volume books that used to take up multiple bookshelves are great sources to learn about things. These days you can find digitized versions such as Encyclopedia Britannica. And honestly, I’m a big supporter of Wikipedia. They are honest when a citation is missing, and it’s a lot harder to edit than we were taught in school. I love starting research on Wikipedia and then going through the sources cited at the end before embarking on further searches around the internet.

Statistical sources. Statistics are a useful tool to learn more, but a bit of caution in that you need to be careful with how you interpret them! You can tell a misleading and convincing story based on an incorrect interpretation. If you find statistics that seem damning about something, but no one seems to talk about, you may be interpreting what it says incorrectly.

Newspapers. The good thing about traditional media is that you can find many sources which will tell you exactly the political leanings of different media outlets. Biased media is almost unavoidable, so as long as you’re aware of it I think traditional media is a fine source, but one that is getting increasingly shoved behind paywalls.

To Conclude: Is media literacy dead or taking a nap?

I’m not sure anything too serious happened to media literacy. I think media has shifted in style so much due to the proliferation of mass media and particularly the internet that our education systems and brains cannot adapt fast enough as a collective. Even 30 years ago, you would likely have a subscription to only one or two newspapers, maybe you would listen to the radio, and then watch the morning and/or evening news on the TV. You had complete control over what you saw and heard, you could choose to opt out of these forms of media and only be exposed if someone happened to talk to you about it that day. The landscape is so different now. You have to go out of your way to not see someone’s opinion. And because there is a lack of opting-in, we can feel burdened and like we’re supposed to engage with all the local and global politics of the day. It can be a huge pressure to have all the information of the world in our pockets.

Instead of looking away, I advocate for people to opt-in. Find sources that you trust and enjoy and carve out time to engage with the content, what I like to call a “controlled scroll”. You can feed the habit of scrolling while looking at news content, simply set a timer and dedicate a few minutes each day to learning about news locally and globally. In addition, make your phone less appealing and addicting to avoid the doom scroll and being inundated with various opinions. Turn off post notifications, mute/unfollow/block accounts, use your phone and app settings to make news and opinion content less jarring. We need to stop fighting against media but instead figure out how to coexist without hampering on an idealized past without the internet.

Sources

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/stereotype

https://www.britannica.com/topic/propaganda

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-55862548

https://www.literacyworldwide.org/get-resources/literacy-glossary

https://www.scribbr.com/working-with-sources/credible-sources

https://library.csuchico.edu/sites/default/files/craap-test.pdf

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/social-sciences/media-analysis

Pingback: How to Become More Politically Literate -